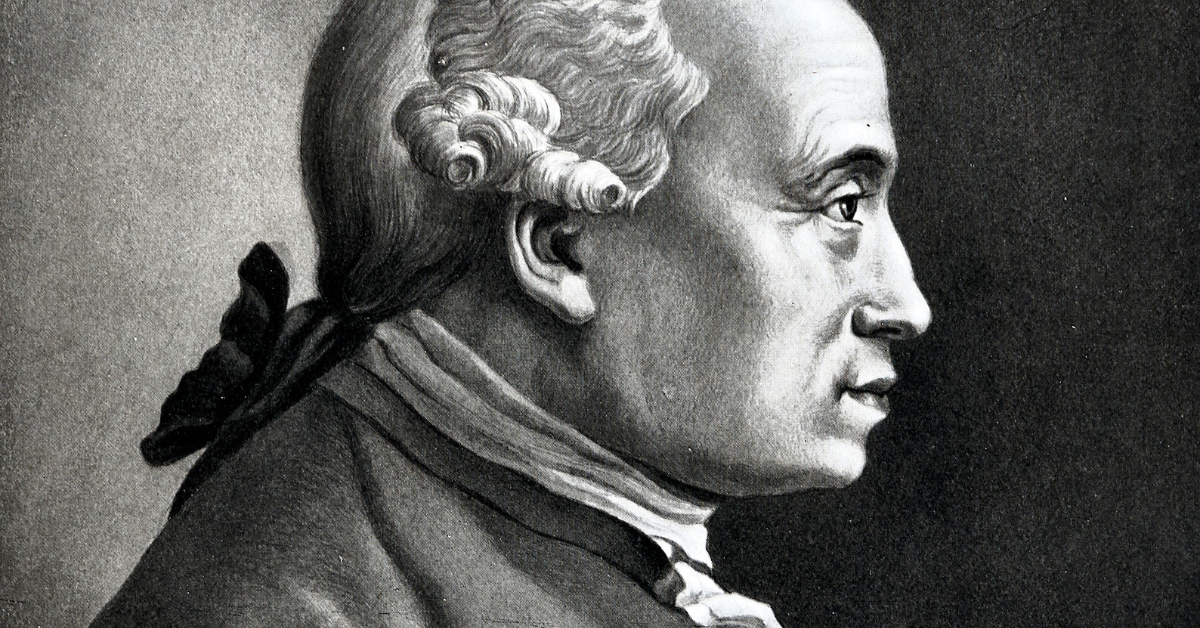

An Introduction to Immanuel Kant: A Beginner’s Manual

Today marks 300 years since the birth of Immanuel Kant in 1724.

Kant is undeniably one of the most influential figures in modern Western philosophy. Through his work, Kant merged the two opposing philosophic traditions of rationalism (think Descartes) and empiricism (think Francis Bacon), thus ushering in a new era in the development of philosophy.

Fun facts about Kant:

Kant was a homebody. Born in Königsberg, Prussia, he never left town. Throughout his life, Kant turned down prestigious opportunities to teach further abroad, including a professorship at Berlin, in favour of the peace and quiet of his home city.

As a young man and a student, Kant lived a life of poverty and deprivation. He was one of nine children (only six of whom reached adulthood) and often went hungry. Kant said he used to stave off ill health by “breathing only through my nose in the winter and keeping the pneumonia winds out of my chest by refusing to enter into conversation with anyone.” And he was barely 5 feet tall!

You wouldn’t think it given his writing style, but Kant was apparently a really fun lecturer! Kant lectured on everything from physics and mathematics—including logic, metaphysics, and moral philosophy to fireworks and fortifications. His lecturing style was humorous and filled with vivid examples from his extensive reading. Every summer for 30 years he also taught a popular course on geography. In fact, Kant was one of the first people to teach geography as a subject in its own right.

Kant hit his peak relatively late in life, publishing his first great Critique when he was 57. From 1781, he started producing an incredible number of original works which revolutionized the study of philosophy.

Kant’s philosophy is notoriously convoluted and difficult to understand. His best-known work, The Critique of Pure Reason, was nearly 800 pages when it was first released and has been called a nearly unreadable philosophic masterpiece. Kant himself described it as “dry, obscure, contrary to all ordinary ideas, and on top of that prolix [tediously lengthy].” When Kant sent the manuscript to a friend, the friend apparently started reading it but couldn’t finish, saying, “If I go on to the end, I am afraid I shall go mad.”

Kant’s daily routines ran like clockwork. The famous German writer Heinrich Heine said that Kant’s life was a “[m]echanically ordered, abstract, old bachelor kind of existence.” Heine continues,

Getting up, drinking coffee, lecturing, eating, going for a walk, everything had its fixed time; and the neighbours knew that it must be exactly half-past four when Immanuel Kant, in his gray frock-coat, with his Spanish cane in his hand, stepped from his door and walked towards the little lime-tree avenue, which is called after him the Philosopher’s Walk.

As Heine pointed out, there’s quite a contrast between Kant’s quiet, mechanical existence and what he calls “his destructive, world-smashing thoughts.”

So what did he think?

It’s almost impossible to reduce Kant’s ideas to bite-sized pieces, but for the sake of this article, we’ll give it a try!

Kant’s most famous distinction was his idea of the phenomenal world (things as they appear to us) and the noumenal world (things as they are in themselves). According to Kant, we can only know things in the phenomenal world— the world of experience. But Kant would also say that man’s capacity to act morally makes no sense unless there’s a noumenal world where free will, God, and immortality exist. Even though we can’t know anything about these things, we can rationally believe they exist, because our moral nature as human beings requires it. As he puts it in the second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant “had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith.”

Moral philosophy:

Kant once wrote, “Morality is not properly the doctrine of how we may make ourselves happy, but how we may make ourselves worthy of happiness.” Kant believed that reason is the source of morality and gives us a fairly severe picture of what morality looks: basically, we must act on the motive of duty alone.

Kant’s famous ‘Categorical Imperative’ is the moral principle that says: “Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law”. Basically, before you do something, you must first ask yourself: ‘What if everybody did it?’ If you can honestly and self-consistently wish that everyone did what you are thinking of doing, then you’re obeying the categorical imperative.

Kant formulates the same idea in a different way when he says, “So act as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in another, always as an end and never as only a means.”

We’re just scraping the surface here. Kant wrote so much on ethics, aesthetics, political philosophy… the list goes on!

Kant died at Königsberg on 12 February 1804. His last words were “Es ist gut” (It is good). 300 years later, Kant’s work in philosophy still has monumental significance, and he stands as one of the giants of Western Civilisation.