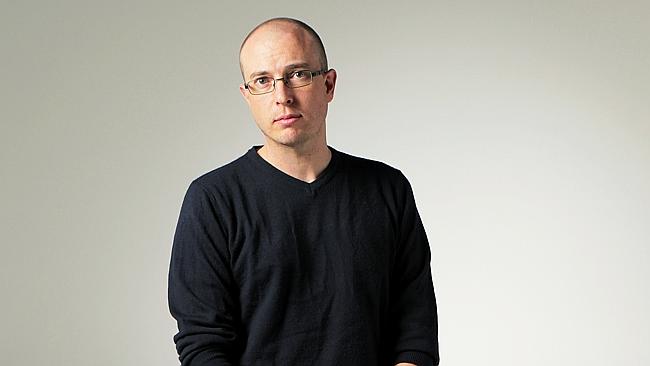

Campion’s Dr. Colin Dray shortlisted for Vogel’s Literary Award

Campion Literature lecturer Dr. Colin Dray was recently shortlisted for The Australian Vogel's Literary Award - a prize worth $20,000 and open to writers under 35, with the winning manuscript published by Allen & Unwin. Dr. Dray's manuscript, Sign, is centred on a boy who loses his voice after a life-saving operation. Here is an excerpt from the work which appeared in The Weekend Australian Review (April 18-19 2015):

Sign

by Colin Dray

Dettie’s operation had not gone so well as Sam’s, and she told him so. The next morning, lying in his hospital bed, his entire body somehow tender, lips cracked and dry, his neck throbbing beneath its bandages, Dettie sat on the edge of the mattress, one hand cupping his knee, as she told him the whole of her story — or at least all that she remembered. She spoke slowly, her voice warm and measured, as if reading him a bedtime story. From the first pinch in her chest, to the searing down her arm; from the thunder and sway of the ambulance; through the stench of ammonia in the operating room; until she woke on the other side of the anaesthesia, bruised and sliced and nauseous, a burning sensation still eating down into her heart. Sam sat in place trying to nod, his head still cloudy, a sting rising up from his jaw, thinking he saw the faintest smile creep at the corner of her mouth.

She’d been lucky, she said. And so had he. And together they would both be stronger than they’d been before. “See, people break sometimes, Sammy,” she said. “Like a toy, or a car, or a bone. Things come apart. But that’s not the end of them. They can be put back together. Fixed up. And you know what? Afterwards, those things are stronger, always, in the broken places.”

Sam blinked, trying now not to move his head at all. She was probably right, he thought, but he didn’t feel stronger yet. What he felt instead was the tape tugging on the skin of his throat. He felt stitches beneath the gauze pulling at his flesh in a hot, itchy throbbing. He could feel the other stitches that were still inside him — string holding his body in place — the ones that the doctor said would disappear over time. He already had the strange chalky taste of them dissolving at the back of his throat. And beneath all of that was a hollow that he had never known before, a cold, empty ache where his voice had once been. Every time Dettie would tell her story, Sam would sit in place, nodding his head as she spoke. He would peer out into the hallway, unable to speak even if he had anything to say, wondering where in that cavernous building his own operation had occurred. Whenever Dettie left he would roll back over on his side, feeling the tape around his bandages tug at his throat, feeling the unseen stitches beneath pull tight at his flesh.

It had started when he was nine years old, after his father moved to Perth. Sam had been having trouble swallowing and started feeling a sharp pain in his ear. By the time he was 10, and his father had stopped sending postcards, he was bald, silent, and blistered with radiation. Long before the surgery, a doctor had explained his condition by showing him a goofy cartoon filled with sneering blue monsters and sword-fighting white blood cells, but as Sam had watched their colours tremble and dance he forgot what all of it meant. His mother had joked about how important he must be to see so many specialists, and Sam felt tall in their waiting rooms when the nurses would smile and wave hello. He was stage two, the doctors decided at last, which meant the cancer had spread and he would have to lose his voice.

A week before the operation he’d almost won a class alphabet game by spelling the words larynx, lymph nodes and laryngectomy. But Mrs Fletcher had made him sit down when he started describing the procedure with a red-tipped pencil. Two months later, after an upper endoscopy that made him gag, two CT scans, four ultrasounds, and an oral surgeon who kept prodding his neck and dipping his greyflecked eyebrows in disapproval, Sam’s final words were, “Batman, because he doesn’t have any superpowers,” as a gas mask slid over his face. Weeks later the liquids, exams and radiation had condensed his saliva into snot.

In his mother’s dresser drawer there was a yellow cassette from when he was younger. On it was a recording of he and his father singing Mary had a Little Lamb . Sam had been thumping the microphone and his father had to keep breaking the melody to get him to stop. ‘‘You had the sweetest little voice,’’ his mother told him once, as though remembering some distant birdcall.

The Campion community is immensely proud of Dr. Dray, who teaches Literature units across all three year levels at the college. We wish him every success with Sign and in his future writing endeavours.

The announcement article was available on The Australian website.